There are endless debates among language teachers about how concerned teachers should be with their students’ language output. What is the best balance between the extremes of correcting most of their errors and correcting none? Do we want students to speak accurately, even if doing so limits their ability to use the language easily? Or do we want them to speak more comfortably (that is, fluently), even at the expense of accurate pronunciation and grammar? How persnickety should the teacher be?

There will always be battles between advocates of accuracy and advocates of fluency. However, most Western language teachers now fall into the latter camp, and they are supported by a large body of research and language theory. According to this point of view, there is in inevitable lag between language fluency and language accuracy. As language learners develop greater comfort in using a second language, they become better able to identify and correct their own mistakes. I believe this principle should dominate language acquisition.

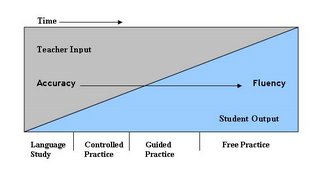

If you want to visualize this idea in practice, take a look at the graphic at the beginning of this post. The upper triangle represents teacher talk, which is always accurate; after all, she is usually a native speaker. The teacher begins class by talking (call this “teacher input”). However, the good teacher steadily reduces her own talk time by introducing activities that increase language production by her students (call this “student output.”) Conceptually, the class quickly changes from one in which the teacher does almost all the communication (focus on accuracy) to one in which the students do almost all the talking (focus on fluency).

As is always the case, a good language lesson should go through several stages as you make the transition from accuracy to fluency. It should begin with language study, then continue with activation of the language through controlled, guided and free practice exercises.

Forget about spending endless hours teaching grammar or having your students repeat sentence patterns by rote. Language acquisition takes place most effectively when your students use it in increasingly life-like situations. As the band leader said in auditions, “Don't play me the scales. Play me a damned tune!”

The focus on accuracy is strongest during the language study phase of class. Here the teacher explains some points of grammar, pronunciation or vocabulary, and does most (if not all) of the talking. There’s little possibility of error, because students don’t say much. This stage of the lesson is short, however.

Teachers need to structure their classes in such a way that they say less and less as class rolls on, while the students say more and more. When they do this, students become increasingly active in later stages of class, the “three practices”.

In controlled practice, the teacher remains in control. Student activities are such that it is fairly difficult for them to make errors – and when they do, the teacher’s job is to make corrections. At this stage, teacher input (also known as “teacher talk time”) is about equal to student output (“student talk time”). But student output completely dominates the latter parts of the class. The teacher relaxes control progressively during guided and free practice activities. Sure, your students will make mistakes, but their fluency will improve. And if you design your activities well, your students will correct each other or themselves when challenged.

I haven’t described all the components of an ideal lesson plan, of course. For example, good classes begin with a warm-up, which serves to switch on the students’ second language brains. They also include a stage often referred to as “engagement” – a few minutes of class in which the teacher catches student interest and generates excitement about the upcoming topic of study.

These notes are barely more than the sketch of a notion, but the basic idea is strong. Let accuracy go in the interest of fluency. If you do, the odds are you will see immediate improvements in your students’ classroom performance.

No comments:

Post a Comment